Malankara Research

Research and reflections on the ancient Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church of Malankara, Kerala

Introduction

The foundation-narrative of this Church, comprising the origins, historical progress, faith and tradition of the Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church of Kerala

The traditions regarding St. Thomas’ arrival in south India, the conversion of indigenous people to Christianity, and the establishment of 7 ½ churches in Kerala at that early date, constitute the commencement of the history and religious identity of the JSOC. This is followed by several other significant milestones in the JSOC’s history that form the continuous narrative account of the foundation and progress of their religion and faith over the past two millennia.

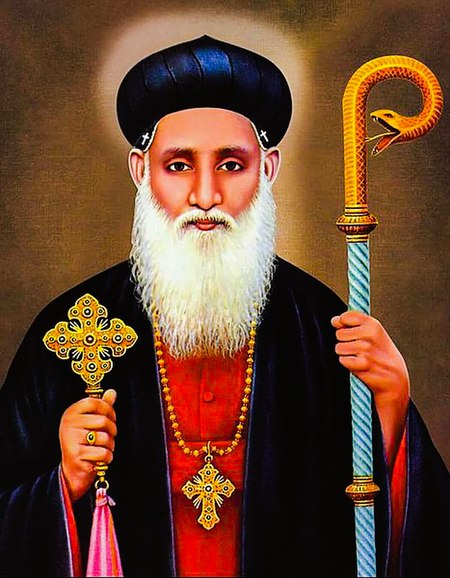

St Thomas

The JSOC believe that the Apostle St. Thomas first arrived in Mylapore at the behest of a king called ‘Chozha Perumal’ in AD 51, from where he boarded ship again and disembarked in their port city of Kudungalloor in AD 52. By preaching the Gospel and performing miracles they believe, he converted a large body of indigenous people to Christianity, established ‘seven-and-a-half’ churches, appointed certain families to perform priestly functions, and finally returned to Mylapore where he was martyred, and that his relics were removed to Edessa in around the turn of the 3rd century.

[left: icon of St Thomas]

Mani and the decline of the community

According to the JSOC accounts, in the third century, the Christian community declined significantly and were under threat of becoming extinct altogether. This decline they believe, was caused by the arrival of Mani, the Persian Gnostic thinker and founder of Manichaeism. Preaching his religion in south India, Mani converted many to his religion, which resulted in the persecuted Christians, who took refuge in Malayala-country on the west coast. They believe that at this critical time, the Christians in Kerala also suffered significant loss of numbers due to persecution and apostasy.

Edessan migration

In 345 CE, a large group of Mesopotamian Christians – led by Mar Joseph, Metropolitan of Edessa, and Knai Thoma, a merchant who had already visited Malabar and found the Christian community there in need of help – came with a large cohort of Christians to settle in Malabar. They won favour with the local king Cheraman Perumal, who granted them land to settle and a Charter of privileges. In this way, the local Christian community were revived, both socially and spiritually. The Edessans brought to Kerala their liturgy and the Syriac language, and the term Syrian Christian stems from this assimilation.

Kollam migration

At another period of great trouble for the local Christian community, another migration of a large group of bishops and Christian families from Mesopotamia took place. This was in 825 CE, and they arrived in the city of Kollam. As with Knai Thoma, they won the grace and favour of the King of Kollam, and received from him various rights and privileges, both social and mercantile. The Charter known as the Kollam Copper Plates given to this group still exist.

Links with Antioch

In the 700-year period between the Kollam migration and the arrival of the Portuguese, the Christian community in Kerala was sustained by the the intermittent arrival of Metropolitans sent by the See of Antioch, either directly by the Patriarch of Antioch, the Supreme Head of the Syrian Orthodox Church, or by his Suffragan, the Catholicos of the East.

Nestorian bishops

One of the controversies in the historical progress of the JSOC in Malabar is the question of whether they adopted Nestorian dogmas from time to time, Nestorianism being a heretical set of beliefs that were historically associated with the Church of the East, and whether they were as a result, under the so-called ‘Nestorian Church of the East’. (This term is firmly rejected by that Church as inaccurate.). The JSOC concedes that some of the bishops who arrived in Kerala in the 16th century were almost certainly Nestorian – particularly Mar Abraham, Mar Joseph Sulaqa and Mar Simeon – but affirm that these bishops were not accepted as their Metropolitans by them. . This was a period when they were under pressure to conform to Rome, and as the ports were blockaded by the Portuguese, the Syrian bishops sent by Antioch were unable to reach Kerala in the 16th century, and so these Nestorian bishops were conditionally accepted, and allowed to carry out certain episcopal functions such as the ordaining priests and the consecration of churches.

The arrival of the Portuguese

The advent of the Portuguese colonial phase in Kerala started the arrival of Vasco Da Gama in 1498. The missionaries that came with the Portuguese navigators and merchants tried to lay claim to the existing churches under the authority of the Pope of Rome. This led to conflict with the indigenous Christians, and this was to reach a defining moment in 1599.

The Synod of Diamper

However, in 1599, the Archbishop of Goa, Alexis de Menezes organised the Synod of Diamper to forcibly bring the JSOC under the authority and jurisdiction of Rome, and adopt Roman Catholicism. The JSOC were accused of heresies (including Nestorianism) and various wrong practices, and put under intense pressure by which they adopted Catholic rites and practices.

Oath of the Leaning Cross

In 1653, following persistent appeals from the JSOC, when the Syrian bishop Mar Ahatalla (believed to be Patriarch Ignatius of Antioch) arrived in South India to rescue the JSOC from Rome, he was imprisoned by the Portuguese and brought to Kochi by ship. Tens of thousands of Syrian Christians rose up in protest, demanding that he be released. But the Portuguese are thought to have drowned him quietly in Kochi harbour that night. Hearing this outrage, about 25,000 Syrian Christians are believed to have gathered at a granite cross near Kochi harbour took an oath rejecting the authority of the Roman Catholic Church. Passing stout mooring-ropes over the cross and extending them in all directions, they are believed to have taken this oath with everyone symbolically holding onto these ropes. With the pull of the masses, the cross tilted on its plinth, which gave this event the name Koonen Kurishu Satyam (the Oath of the Leaning Cross).

The re-establishment of the Syrian Orthodox Church in Kerala

After the Oath of the Leaning Cross, in accordance with the directions given by Mar Ahatalla before his death, the Syrian Christians consecrated their then Archdeacon as Bishop Mar Thoma I. The main body of the Syrian Christians returned to their Syrian rites and liturgy, and also continued to appeal to Antioch for help. In 1665 Mar Gregorius Abd’ al Jaleel, Patriarch of Jerusalem (who was under the See of Antioch, the title ‘Patriarch’ being an honorary one in recognition of Jerusalem being the foremost city in Christendom,) arrived, followed by the Maphrian (or Catholicos of the East) Baselius Yaldo and Bishop Mar Ivanius in 1685, and these hierarchs were instrumental in fully restoring to the JSOC, the faith, doctrine and practices of Antioch, as well as its Apostolic Succession.

Clarification of terms

Every element of the name of this Church in Kerala needs some clarification – ‘Malankara’, ‘Jacobite’, ‘Syrian’, and ‘Orthodox’. Click below for more information.

The faith and historical narrative of Christians of the Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church of Kerala, as articulated by them and passed down over the generations.